CONTENTS

- What is the normal anatomy of the colon?

- Is colon cancer a common disease?

- What is colon cancer and how does it develop?

- Can colon cancer be prevented?

- What are the signs and symptoms of colon cancer?

- How is colon cancer diagnosed?

- What is the importance of staging in colon cancer?

- How is colon cancer treated?

- What is the life expectancy in colon cancer?

- How is follow-up performed after colon cancer treatment?

For most types of cancer, the slogan is: “DO NOT BE AFRAID OF CANCER, BE AFRAID OF BEING LATE.”

This means that in the vast majority of cancer types, there is no early warning symptom before cancer develops. There is only the hope of detecting an already existing cancer at an early stage before it spreads.

However, for colon cancer, the slogan is more ambitious:

“COLON CANCER IS A PREVENTABLE DISEASE.”

If you patiently read the following sections, you will better understand how this is possible.

Colon cancer is one of the cancers of the digestive system for which modern medicine has achieved the greatest success. If you have been diagnosed with colon cancer and the disease has been detected at an early stage, your chance of having a long and healthy life is very high. Even in cases where colon cancer has spread to distant organs, highly successful results can still be achieved. Therefore, you should never lose hope.

Colon cancer is a general diagnosis. Even though the cell type may be the same, cancer can behave differently from one person to another. In other words, the same type of cancer may follow a different course in two patients with the same diagnosis. Therefore, a poor outcome experienced by another patient is not a measure for your own disease. Always take good examples as your reference.

Share your illness only with your doctors who are helping you in fighting with your cancer and with relatives you trust. Everyone around you will inevitably have stories and opinions about cancer. Do not allow unnecessary comments and experiences of people who cannot contribute to your treatment to harm your morale. Fighting cancer requires endurance, patience, and morale, as it is a long process.

In this informational text, detailed statistical data such as survival times derived from statistics in colon and rectal cancers will not be discussed, as these issues are more appropriately discussed between the patient and the treating physician.

You may frequently encounter the words cancer and tumor used together in this text. Although tumor literally means “swelling,” here the terms cancer and tumor are used interchangeably, such as colon cancer or colon tumor. They mean the same thing.

WHAT IS THE NORMAL ANATOMY OF THE COLON?

The colon is a large organ, and treatment approaches may vary depending on the location of the cancer. Therefore, it is useful to have some basic knowledge of its anatomy. The final part of the digestive system consists of the colon (large intestine) and the rectum. Although diseases of these regions are often mentioned together, colon and rectal cancers differ in both symptoms and treatment. For this reason, they will be discussed under separate headings.

The large intestine continues from the small intestine. There is a functional valve (the ileocecal valve) between the small and large intestines. From this point, the large intestine begins and eventually reaches the anus, where it is called the rectum. The appendix is a finger-like extension at the end of the cecum. Appendix cancers exist but differ from colon cancers and will not be discussed here.

Because the intestines are mobile and flexible, precise measurements are difficult. The length from the cecum to the rectum is approximately 100–150 cm. The rectum, including the anus, is about 12–15 cm long, and the anal canal is considered to be 3 cm in surgical terms. The large intestine frames the abdominal cavity, surrounding the small intestines. The right side is called the right colon, the portion crossing the abdomen is the transverse colon, and the left side is the left colon. Colon cancers are named according to their site of origin (e.g., cecal tumor, right colon tumor, left colon tumor).

IS COLON CANCER A COMMON DISEASE?

In Western countries, colon cancer is the third most common cancer in both men (after prostate and lung cancer) and women (after breast and lung cancer). Each year, 50–70 out of every 100,000 people are diagnosed with colon cancer. Most patients are over the age of 60. However, due to urban lifestyles, poor dietary habits, chemical exposure, and environmental pollution, incidence at younger ages is increasing.

The lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer is approximately 6% for individuals with average risk. If a person has close relatives with colon cancer, especially more than one, the risk increases 3–4 times. In certain inherited genetic conditions, the risk can approach 100%.

WHAT IS COLON CANCER AND HOW DOES IT DEVELOP?

All cells in our body have a lifespan. When a cell ages, a new identical cell is produced according to genetic rules. Healthy cell renewal depends on the harmonious function of various genes. Some genes act like guards, eliminating faulty cells, while others detect incompatible genetic coding and remove cells prone to cancer.

When genetic defects occur during cell renewal, a group of cells may escape the body’s control system and begin to multiply uncontrollably. This uncontrolled cell growth is, in its simplest form, cancer. Colon cancer begins with abnormal cell proliferation in the mucosal layer lining the colon. Over time, these cells grow, become cancerous, invade neighboring tissues, and spread to distant organs via blood and lymphatic vessels (metastasis).

Most colon cancers arise sporadically due to environmental factors rather than inherited genetic defects. Some are familial, caused by inherited genetic mutations, and rarely, they arise as complications of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

Abnormal tissue growth caused by genetic dysfunction is called a polyp. Polyps may grow and, over time, accumulate additional genetic defects that lead to cancer. The longer a polyp remains and the larger it becomes, the higher the risk of cancer transformation—typically over more than 10 years. This is why routine colonoscopy is recommended every 10 years if no abnormalities are found. However, not all polyps become cancerous.

CAN WE PREVENT COLON CANCER?

If the factors that cause colon cancer are known, it may be possible to protect ourselves from it. During the renewal of normal tissue, a series of genetic defects can occur that cause differentiation in newly formed cells which should actually be exact replicas of the original ones. What are the causes of these genetic defects?

- Poor nutrition

- A diet low in vegetables and high in meat (Meat products move slowly through the intestines, and during this prolonged transit the contact time between cancer-causing [carcinogenic] substances and the intestinal wall increases. Vegetables, on the other hand, leave the intestines more quickly. In addition, the antioxidants they contain help prevent cancer formation. Indeed, the incidence of colorectal cancer is much higher in Western countries with meat-heavy diets than in African countries where vegetable-based diets are predominant.)

- Meat products that are fried to the point of burning, with carbonization on the surface

- Exposure to toxic substances

- Smoking

- Chemical substances (such as solvents used in the paint industry)

- Inherited defective genes: A genetic disorder known as Lynch syndrome, in which cancers of organs outside the colon may sometimes accompany colon cancer. In family members with this syndrome, cancer does not arise from a precursor lesion such as a polyp; instead, it begins directly from the tissue without polyp formation.

- Inflammatory bowel diseases (Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease): In these diseases, there is only a possibility of creating a predisposition to cancer. It is not correct to assume that cancer will definitely develop. One should simply be aware of this risk, and the disease should be carefully followed by a Gastroenterology Specialist.

Thus, when we say “colon cancer is a preventable disease,” what is meant is primarily protection from these cancer-causing factors. Paying attention to dietary habits and cooking methods, and avoiding carcinogens such as smoking, are the first precautions. Despite all these measures, polyps may still develop. At this point, screening tests come into play. These are examinations that should be performed on everyone over the age of 50, even if they have no complaints or family history of cancer.

What are the screening tests?

- Fecal occult blood test:

This is the most practical population screening test. It detects whether there is blood in the stool. It is an easy test and can be done at home. After a small amount of stool is applied to the test card, a color change occurs if blood is present. In this case, colonoscopy is recommended for detailed examination. However, the test may yield misleading results—showing “no problem” when there is one, or “a problem” when there is none. Even if the test is negative, the presence of bowel complaints or visible blood in the stool does not mean “there is nothing wrong.” In such cases, the test result is disregarded and a colonoscopy is absolutely necessary. - Endoscopic examinations (sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy):

These are the most reliable tests, as the entire colon can be directly visualized with a camera. Tissue samples (biopsies) can be taken from any suspicious lesion for examination (2). There are many urban myths about colonoscopy, such as “it is very painful,” “they do it while making you scream,” or “bowel preparation is a disaster.” Please do not listen to these inaccurate statements. Obtain correct information from your doctor. - Radiological examinations (barium enema colonography):

Nowadays, this is preferred only for patients who have conditions that prevent colonoscopy. It is no longer used as a screening test.

Thus, if a polyp is detected during evaluation—either because of blood in the stool or as a preventive measure in someone over 50—and if this lesion with malignant potential is removed, the risk of developing cancer is eliminated. If cancer cells are already present within a detected polyp, the approach differs. I will address this topic in detail in another post. Removal of polyps is called polypectomy and can be performed endoscopically (via colonoscopy) without the need for surgery. In this way, sporadic colon cancers—those arising largely from external factors and constituting the majority of colon cancers—can be prevented before cancer actually develops.

I would like to emphasize again: THE CANCER HAS NOT BEEN DETECTED EARLY. A DANGEROUS TISSUE WITH THE POTENTIAL TO BECOME CANCEROUS HAS BEEN DETECTED AND REMOVED BEFORE IT HAD THE CHANCE TO TURN INTO CANCER.

Here, I would also like to open a parenthesis regarding Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (FAP). This disease results from a genetically inherited defect. In a child born with this gene, polyps begin to develop in the colon starting around the age of 12. The number of polyps may exceed 100, even reaching thousands. One or more of these polyps will inevitably become cancerous before the person reaches their 40s, leading to death. However, if this familial risk is known, children in the family are monitored from the age of 12. If they carry the defective gene, once they complete their development—in their early 20s—the colon and rectum, which are the target organs of the genetic defect, are surgically removed. Thus, since the entire colon is removed before the polyps can become cancerous, colon cancer ceases to be a destiny for this individual, and they can have a chance at life similar to others. The surgical technique used for this disease differs in some respects from those used for other colon cancers. This will be discussed in the treatment section.

On the other hand, in another type of colon cancer caused by an inherited genetic defect (Lynch syndrome), polyps are absent. However, because the cancer risk within the family is known, children in these families are periodically monitored with colonoscopic examinations starting at the age of 20.

In patients with chronic bowel diseases such as Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease, periodic follow-up and repeated biopsies are performed. If signs of malignant transformation (dysplasia) are detected, surgical intervention is undertaken.

WHAT ARE THE SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF COLON CANCER?

Symptoms and findings vary depending on the location of the cancer within the colon:

- Bleeding:

This is the most common and important symptom. If the cancer develops in the part of the intestine close to the anus, the patient notices fresh red blood mixed with the stool. The term “fresh red blood” may seem surprising—you might think blood is always red. However, blood that has remained in the intestine can become dark or even black, indicating bleeding from higher levels of the intestine or even the stomach. Here, what is meant is blood that comes from a region very close to the anus and passes with the stool before there is enough time for darkening, so it remains bright in color. This is a very alarming sign. Anyone who sees blood in the stool naturally fears cancer. As emphasized earlier, in cancer the blood is usually mixed with the stool. However, not all blood mixed with stool is necessarily a sign of cancer. Dripping bleeding during or after defecation, or blood seen on toilet paper during cleaning, is usually indicative of benign conditions such as hemorrhoids or fissures. Nevertheless, differential diagnosis must always be made by a General Surgery Specialist.

In cancers developing in the first part of the colon (right colon, farther from the anus), bleeding usually breaks down within the stool before defecation and becomes unnoticeable. Therefore, it is called occult bleeding and can only be detected with a fecal occult blood test. Over time, this leads to anemia.

- Fatigue and early tiredness:

When occult bleeding goes unnoticed for a long time, symptoms of anemia such as fatigue and easy exhaustion appear. Therefore, when an elderly patient presents with these complaints, we always perform a blood count. If anemia (iron-deficiency anemia) is detected, colonoscopic examination is mandatory. This is a golden rule. An elderly person who is anemic and easily fatigued should be suspected of having colon cancer until proven otherwise. Only after colon cancer is ruled out by colonoscopy are other causes investigated. - Changes in bowel habits:

Cancers developing in the part of the colon close to the anus (left colon) cause narrowing due to tumor growth, since this part of the colon has a smaller diameter compared to other segments. As a result, bowel habits are disrupted. The patient may complain of constipation, pencil-thin stools, passing stool in small fragments, or even alternating periods of constipation and diarrhea. - Pain and intestinal rumbling:

As the growing cancer tissue (tumor) narrows the intestinal passage, stool has difficulty passing, leading to cramp-like pain due to contractions. Those who have experienced kidney stones or labor pains often compare the pain to those experiences. Sometimes, increased bowel movements and audible rumbling may also be heard due to difficulty in passage. - A palpable abdominal mass:

Rarely, the tumor may grow large enough to be detected by palpation during abdominal examination. This finding is more common in tumors developing in the right side of the colon. Cancers on the right side tend to form masses, whereas tumors on the left side tend to constrict the bowel and cause obstruction without forming a large mass.

HOW IS COLON CANCER DIAGNOSED?

When suspicion arises based on symptoms and physical examination findings, colonoscopy must be performed. If a tumor is detected during colonoscopy, biopsies are taken, and the definitive diagnosis is established through biopsy.

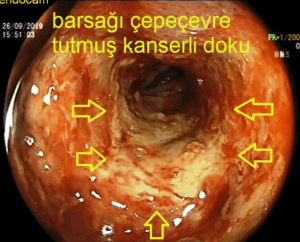

Image: Endoscopic appearance of colon cancer.

At this point, the name of the problem has been identified. However, the choice of treatment depends on how widespread the disease is. Colonoscopy only shows the extent of the tumor within the inner wall of the intestine (details about colonoscopy can be found under the endoscopy section of our website). As mentioned earlier, the tumor does not grow only inward into the intestinal wall. It may extend beyond the originating wall to invade neighboring organs. It can also spread through blood and lymphatic vessels to nearby lymph nodes and distant organs such as the liver and lungs. Detecting these findings is of great importance in planning treatment—that is, determining the stage of the disease.

At this stage, the most important diagnostic tool is Computed Tomography (CT) (3). During this examination, contrast material (a visible agent on imaging) is administered both intravenously and orally. CT imaging reveals how deeply the tumor invades the intestinal wall, its size, and whether it has spread to neighboring or distant organs. Another important test used in staging is Positron Emission Tomography (PET). In this test, a nuclear substance labeled with a type of sugar is injected intravenously. Since tumor cells avidly take up sugar, the sugar-labeled nuclear substance accumulates particularly in tumor tissue, and on tomographic imaging the tumor and any metastases appear as glowing foci.

WHAT IS THE IMPORTANCE OF STAGING IN COLON CANCER?

As with all types of cancer, the stage of colon cancer is of great importance in determining both the treatment approach and life expectancy. Colon cancer is evaluated in four stages. Broadly speaking, if the disease is limited to the tissue from which it originated, it is considered early stage (Stage I and II); if it has spread to nearby lymph nodes, it is classified as Stage III; and if it has spread to distant organs, it is classified as Stage IV. As can be understood, the best chance of treatment success and long-term survival is seen in the early stages (Stage I and II), while expectations are lowest in Stage IV.

Figure. Staging of a colon tumor based on its spread within the bowel wall and to lymph nodes

Stages of Colon Tumors:

- Stage I: The tumor is limited to the innermost layer of the large intestine (mucosa).

- Stage II: The tumor has penetrated deeper into the bowel wall and has passed beyond the muscle layer.

- Stage III: In addition to deep invasion of the bowel wall, cancer cells are found in the lymph nodes.

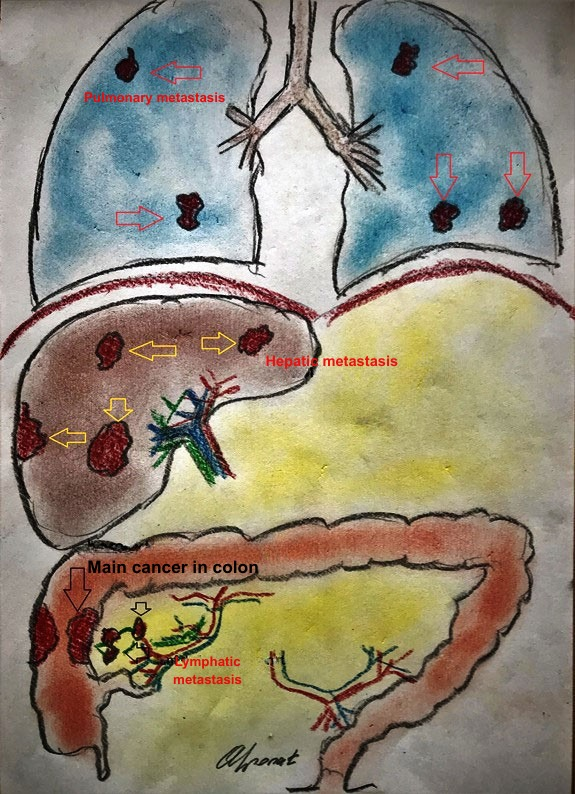

- Stage IV: The tumor in the bowel has spread to distant organs such as the liver and lungs.

Figure. Metastases of a tumor in the right colon to the liver and lungs (Stage IV cancer)

HOW IS COLON CANCER TREATED?

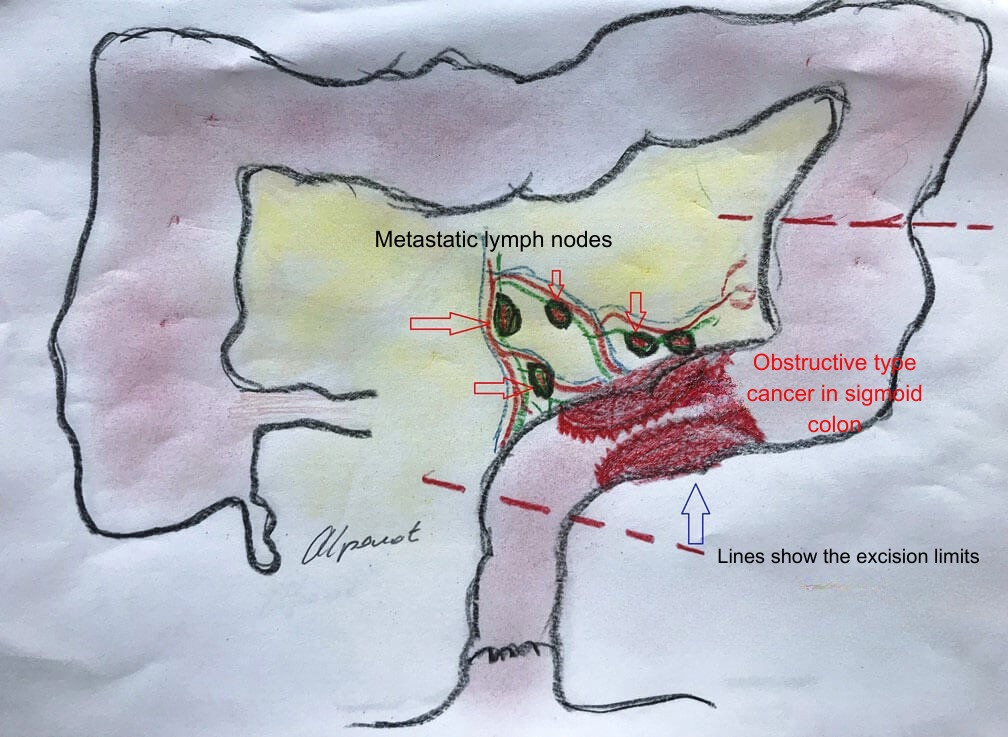

When colon cancer is diagnosed in the first three stages, treatment is primarily surgical. If the tumor is located in the right half of the colon, the right half is removed; if it is in the left half, the left half is removed. Rarely, cancer may develop simultaneously in several different parts of the colon (synchronous tumors). In such cases, the portion of bowel to be removed may differ.

During removal of the cancerous bowel segment, adjacent lymph nodes are also removed. The purpose of this is to eliminate lymph nodes that may already contain cancer cells. If only the tumor-bearing bowel is removed and the lymph nodes are not cleared, residual cancer cells in the lymph nodes may grow and cause early local recurrence.

Bowel continuity is restored by connecting the remaining ends of the bowel. If pathological examination shows no lymph node involvement, no additional treatment is required after surgery. However, if lymph node metastasis is present, chemotherapy is required after surgery.

If the disease has spread to distant organs (Stage IV), the treatment plan is determined individually based on the extent of metastasis and the patient’s overall condition. In suitable patients, both the primary colon tumor and metastatic lesions in distant organs may be surgically removed or destroyed using methods such as radiofrequency ablation, followed by chemotherapy.

One of the most common concerns among patients undergoing colon cancer surgery is the possibility of having to carry a colostomy bag on the abdominal wall. In general, regardless of the location of the colon tumor, the need for a permanent colostomy is almost nonexistent. A stoma becomes necessary only when, after removal of the cancerous bowel segment, the remaining healthy bowel near the anus is not long enough to allow reconnection. This situation may occur in cancers located very close to the anus in the rectum.

In colon tumors, the need for a stoma may arise temporarily in cases causing bowel obstruction that require emergency surgery. Normally, bowel cleansing with laxatives before surgery is standard practice. This allows safer reconnection of the cleaned bowel segments and reduces the risk of leakage. In emergency cases with complete bowel obstruction, preoperative cleansing is not possible. Therefore, after removing the obstructing tumor, the upper bowel segment filled with stool is brought out through the abdominal wall into a bag to allow stool drainage. This stoma is temporary and, at a later date, the bowel is reconnected, allowing the patient to pass stool normally again.

Figure. Cancer tissue causing complete bowel obstruction (top) and temporary colostomy after tumor removal (bottom)

Use of Stents in Colon Tumors

In cases of complete bowel obstruction caused by colon tumors requiring emergency surgery, a temporary stoma may be unavoidable. An alternative to emergency surgery is the endoscopic placement of a metal stent into the obstructed segment. This relieves the obstruction without immediate surgery. The bowel can then be cleansed with laxatives, and in a single planned operation, the tumor can be removed and bowel continuity restored.

Figure. Relief of obstruction with a temporary stent

IS ENDOSCOPIC TREATMENT OF COLON CANCER POSSIBLE?

If the cancer tissue is detected on a broad-based polyp and is limited to the innermost layers of the bowel (mucosa and submucosa), it can be removed endoscopically. This procedure is called Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection (ESD). With this method, the patient can be cured without surgery.

However, it is crucial to note that if the cancer has reached the muscle layer of the bowel, this procedure is not suitable. In such cases, there is a high risk of bowel perforation, leaving behind cancer tissue, and early recurrence due to possible lymph node metastasis.

In Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP), surgical treatment differs significantly from other colon cancers. Even if cancer originates from a single site, the entire colon and rectum must be removed. The small intestine and anal canal are preserved. If only the cancerous segment were removed, cancer would eventually develop from remaining polyps. To prevent severe diarrhea, a pouch (ileal pouch) is created from the last 20–30 cm of the small intestine and connected to the anal canal, allowing stool storage and reducing bowel movement frequency.

WHAT IS LIFE EXPECTANCY IN COLON CANCER?

Colon cancer is one of the digestive system cancers that modern medicine can treat most effectively. The stage at diagnosis is critically important. In early stages (Stage I and II), when cancer cells are confined to the colon wall, the disease can almost always be completely cured.

If cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes (Stage III), cure is still highly possible with surgery followed by intravenous chemotherapy. If cancer has spread to distant organs such as the liver or lungs (Stage IV), treatment options may include chemotherapy alone or a combination of surgery and other methods to remove or destroy metastatic lesions, depending on the patient’s condition. Chemotherapy is always included.

Treatment decisions should not be based on internet information or anecdotal experiences. The purpose of this article is only to provide preliminary information. Proper management requires specialized training in surgery and colorectal surgery. Therefore, treatment should be guided only by qualified specialists.

HOW IS FOLLOW-UP PERFORMED AFTER COLON CANCER TREATMENT?

Follow-up of patients who have undergone surgery for colon cancer is conducted by a medical oncologist, regardless of whether chemotherapy is required. The surgical team periodically evaluates the patient for any issues requiring surgical intervention. Follow-up is conducted according to international cancer surveillance guidelines.

These include radiological imaging, blood tests, and colonoscopic examination of the remaining bowel, scheduled at intervals determined by the treating physicians. Since recurrence is more common in the first two years, follow-ups are more frequent during this period. Surveillance continues for at least five years, after which lifelong follow-up is maintained at longer intervals.

SUMMARY

- Colon cancer is one of the most common cancers.

- Poor nutrition is one of the most important risk factors.

- Screening should begin after age 50, even in the absence of symptoms.

- Screening age varies in genetic syndromes and chronic bowel diseases.

- Fecal occult blood testing is the most suitable population screening test.

- Persistent rectal bleeding requires colonoscopy, even at a young age.

- Most colon cancers arise from polyps; removing polyps during colonoscopy prevents cancer.

- The goal is not only early detection but prevention.

- Prognosis is directly related to the stage at diagnosis; early diagnosis is crucial.

- Surgical removal of cancerous tissue is the most effective treatment; chemotherapy is added when necessary.

- Patients should ask their surgical team about postoperative follow-up and choose physicians who work collaboratively.

- Remember: the same cancer may behave differently in different patients. Do not lose hope due to negative experiences shared by others

Hello, I am Prof. Dr. Ahmet Alponat, a General Surgery Specialist. I provide patient care in the fields of Laparoscopic Surgery, Gastrointestinal and Breast Oncologic Surgery, and Interventional Endoscopy.

You can receive services both at Acıbadem Kocaeli Hospital and at my private practice in Bodrum. To contact me, please visit the Contact page. If you have any questions about the article you have read, you may submit them using the question and comment form located at the bottom of the page.