Is gallstone formation in the gallbladder a common problem?

What is the anatomy of the gallbladder and bile ducts like?

How do gallstones form?

Gallstones:

- What complaints do they cause?

- What clinical conditions do they lead to?

- Which laboratory findings are affected?

Which radiological examinations are used to evaluate gallstones?

Is there a relationship between gallstones and pregnancy?

What is the relationship between gallstones and pancreatitis?

What complications are caused by gallstones?

How are gallstones treated?

Does removal of the gallbladder cause any problems?

Is there a relationship between gallstones and gallbladder cancer?

IS GALLSTONE FORMATION A COMMON PROBLEM?

Gallstone formation is a common and significant health problem that may require surgical intervention. In Western societies, it affects approximately 10% of the population. The likelihood of gallstone formation increases with age. It is estimated that about 20% of people in their 40s and about 30% of those in their 70s have gallstones. Although gallstones are more common in women at younger ages, the incidence becomes similar between men and women at older ages. Nearly half of individuals known to have gallstones eventually require surgery due to recurrent symptoms or the development of complications. Gallbladder surgery is one of the most frequently performed operations worldwide (1).

People with gallstones may simultaneously have stones in the common bile duct. These stones may have migrated from the gallbladder over time or may have formed primarily in the bile duct. The likelihood of this increases with age: approximately 2% in young patients and about 25% in those over 70 years of age. Therefore, when intervention on the gallbladder is required in elderly patients, the common bile duct must also be examined in detail.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY OF THE GALLBLADDER AND BILE DUCTS

The liver is often referred to as the body’s chemical laboratory. It produces bile, which contains by-products of metabolic processes and bile acids essential for fat digestion, and sends it to the intestine. Approximately 1 liter of bile is produced daily and transported to the intestine via the bile ducts.

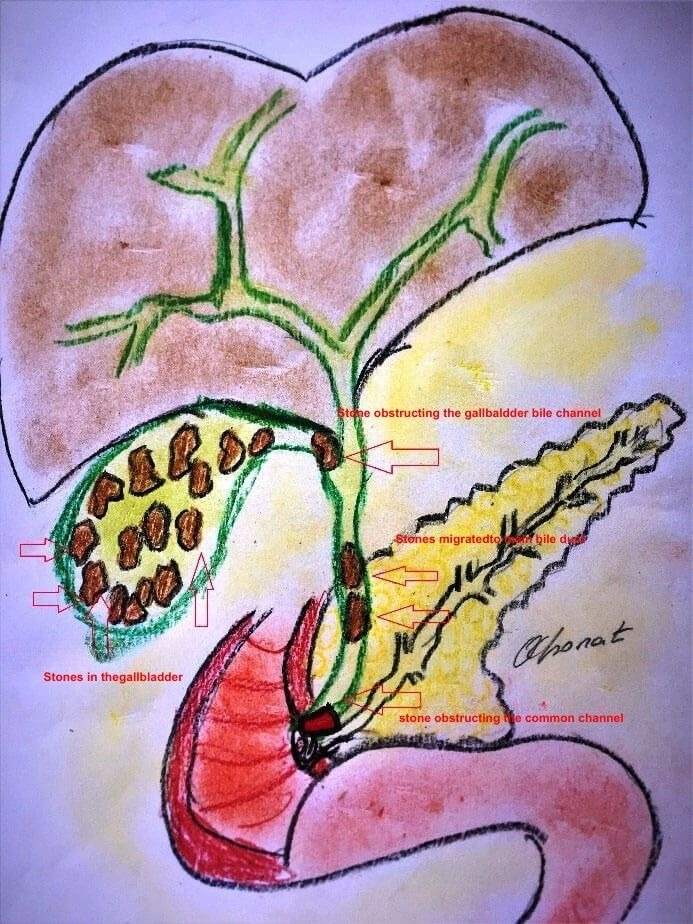

Within the liver, very fine bile ducts originating from liver cells merge to form larger channels. These channels exit the liver and join with the cystic duct from the gallbladder to form the common bile duct. The extrahepatic bile duct is approximately 12–15 cm long and less than 6 mm in diameter; larger measurements indicate bile duct dilatation. In most individuals, the common bile duct joins the pancreatic duct (though they may rarely open separately) and empties into the intestine.

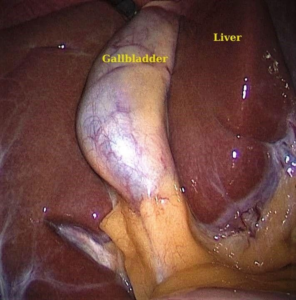

The gallbladder is an organ attached to the underside of the liver and can store approximately 50 cc of bile. It connects to the common bile duct via the cystic duct and receives its blood supply from the cystic artery. When fatty foods pass from the stomach into the intestine, hormonal stimulation causes the gallbladder to contract and empty bile into the common bile duct. A gallbladder filled with stones cannot empty completely during contraction, leading to pain.

HOW DO GALLSTONES FORM?

Gallstones are mainly composed of cholesterol crystals (cholesterol stones) or calcium salts (pigment stones). While cholesterol and black pigment stones form in the gallbladder without inflammation, brown pigment stones form in an inflamed gallbladder.

The metabolic defect underlying stone formation is excessive concentration (precipitation) of bile. This may result from excessive cholesterol secretion or a deficiency of bilirubin salts that normally keep cholesterol dissolved. Cholesterol is insoluble in water, whereas bilirubin salts make it soluble. When this balance is disrupted, cholesterol precipitates within mucous secretions (mucin) from the gallbladder wall, forming biliary sludge. This sludge acts as a nucleus for stone formation. Over time, layers accumulate on this nucleus, forming stones that gradually enlarge (2).

Risk factors for gallstone formation include obesity, diabetes mellitus, excess estrogen, pregnancy, and certain blood disorders associated with increased destruction of blood cells. A well-known clinical mnemonic for risk factors is the “5 F rule”: Fat, Female, Fertile, Fair, Forty.

WHAT SYMPTOMS DO GALLSTONES CAUSE AND HOW DO PATIENTS PRESENT?

The disease caused by gallstones in the gallbladder is called cholecystitis. Gallstones may present in two ways:

- Chronic cholecystitis: intermittent pain, bloating, and indigestion

- Acute cholecystitis: sudden severe pain, fever, nausea, and vomiting—an emergency condition

Pain

Pain is the most prominent symptom. It is felt in the right upper abdomen beneath the ribs and toward the epigastrium. It usually begins about 30 minutes after a heavy meal and may radiate to the back or right shoulder. The pain is typically colicky, increasing and decreasing in intensity. In chronic cholecystitis, it usually resolves spontaneously within about 3 hours, whereas in acute cholecystitis it may persist continuously for hours or even days.

This pain, especially when felt beneath the chest, may sometimes be mistaken for a heart attack. Since similar pain can occur in myocardial infarction, misattributing the pain to gallbladder or gastric causes can delay diagnosis and lead to life-threatening outcomes.

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting may accompany the pain. Vomiting often contains recently ingested food or may present as dry retching.

Bloating and Gas

Postprandial bloating, excessive gas, and belching are common, especially in chronic cholecystitis.

Fever

Fever may occur in acute cholecystitis due to inflammation. Fever is not expected in chronic cholecystitis.

Jaundice

Jaundice occurs when a stone migrates into and obstructs the common bile duct. Rarely, it may also develop due to acute gallbladder inflammation affecting intrahepatic bile ducts. Patients first notice darkening of the urine (“tea-colored urine”), followed by yellowing of the sclera and eventually the skin. Prolonged jaundice may cause severe itching due to bile salt deposition in the skin.

Incidentally Detected (Asymptomatic) Gallstones

Gallstones discovered incidentally during imaging for unrelated conditions are termed “silent” or asymptomatic stones. Although considered asymptomatic, many patients may have long-standing bloating and gas after meals that they attributed to gastrointestinal issues rather than gallbladder dysfunction.

Surgery is not mandatory for asymptomatic gallstones. Only about 35% of such patients will develop symptoms or complications requiring surgery during their lifetime; the remaining 65% will never need surgery. However, surgery is recommended in certain cases even for asymptomatic stones, such as stones larger than 2 cm, presence of diabetes, hematologic disorders, candidates for bariatric surgery, or patients undergoing colorectal surgery (1).

Diabetic patients deserve special consideration. Because pain perception may be reduced, symptoms can be subtle while the disease progresses insidiously to severe infection. Therefore, surgery may be recommended even in asymptomatic diabetic patients.

LABORATORY FINDINGS IN GALLSTONES

In chronic cholecystitis, significant laboratory abnormalities are not expected. In acute cholecystitis, leukocytosis and elevated liver enzymes (AST, ALT, GGT) may be observed. Obstruction of the bile duct leads to elevated bilirubin levels.

RADIOLOGICAL EXAMINATIONS

Ultrasonography is the most effective imaging modality for gallstones. When stones in the common bile duct are suspected, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is appropriate. However, if clinical and laboratory findings strongly suggest bile duct stones, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) should be preferred instead of MRCP.

GALLSTONES AND PREGNANCY

During pregnancy, the incidence of gallstones ranges from 3% to 10%. Increased levels of estrogen and progesterone delay gastric and gallbladder emptying and increase cholesterol production, facilitating cholesterol precipitation and stone formation (3).

Gallstones during pregnancy are often asymptomatic but may cause symptoms. Surgery during pregnancy is associated with increased risks of preterm labor and miscarriage. Therefore, surgery is usually postponed until after delivery unless symptoms are severe. If surgery is unavoidable, it is generally considered after the sixth month of pregnancy.

GALLSTONES AND PANCREATITIS

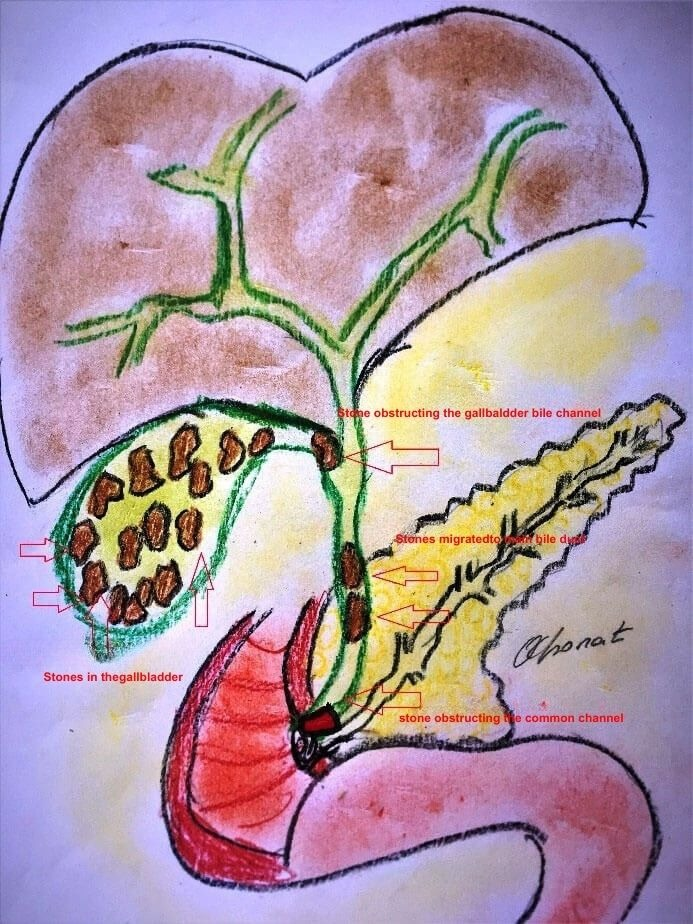

Pancreatitis is the autodigestion of the pancreas by its own enzymes. The connection lies in anatomy: the common bile duct and pancreatic duct usually merge before emptying into the intestine. If stones or biliary sludge obstruct this shared channel:

- Bile cannot drain into the intestine and enters the bloodstream, causing jaundice.

- Pancreatic secretions reflux into the pancreas, causing pancreatitis.

Pancreatic enzymes become activated, leading to inflammation. Blood levels of amylase and lipase increase. While pancreatitis often resolves spontaneously, it can sometimes be severe and life-threatening. Gallstones are the most common cause of pancreatitis.

COMPLICATIONS OF GALLSTONES

Acute cholecystitis: Obstruction of the cystic duct causes gallbladder distension (hydrops), infection with pus formation (empyema), impaired blood supply leading to gangrene, and ultimately perforation, resulting in bile peritonitis.

Migration of stones into the common bile duct: This can cause jaundice, cholangitis (bile duct infection), or pancreatitis.

Fistula formation: Large stones may erode the gallbladder wall and adjacent organs, forming abnormal connections. One example is Mirizzi syndrome, involving a fistula between the gallbladder and bile ducts. Stones may also pass into the intestine, causing bowel obstruction (gallstone ileus) (4).

TREATMENT OF GALLSTONES

Medical treatments aimed at dissolving stones have been tried but abandoned due to low success rates and side effects. Today, the only definitive treatment for suitable patients is surgical removal of the gallbladder.

Early attempts focused on removing stones alone, but recurrence was common. Since the late 19th century, complete removal of the gallbladder (cholecystectomy) has been the standard. Removing only the stones is no longer accepted.

The preferred technique today is laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Compared to open surgery, it involves smaller incisions (usually four, the largest being about 1 cm). Smaller incisions result in less pain, fewer wound complications, better cosmetic outcomes, and earlier discharge—often the next day (5).

In selected patients, laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed as day surgery with safe outcomes (6). However, this approach may not be suitable for patients with significant comorbidities.

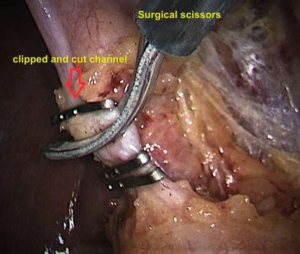

Despite extensive experience, conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery may be necessary in up to 15% of cases, usually due to severe inflammation, unclear anatomy, bleeding, or organ injury. Conversion should be viewed as a safety measure, not a failure (8).

When gallstones cause obstructive jaundice and/or pancreatitis, bile duct stones are first removed endoscopically by ERCP. If pancreatitis is mild or absent, laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be performed within 24 hours. In severe pancreatitis, surgery should be delayed until recovery.

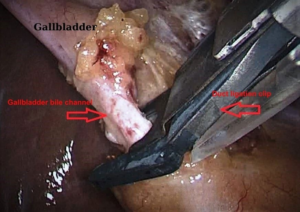

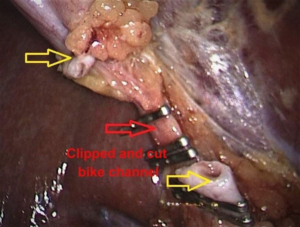

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE (LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY)

A 1 cm incision is made below the umbilicus, and carbon dioxide gas is insufflated to create working space. Additional small incisions are made for instruments. The cystic duct and artery are identified, clipped, and divided. The gallbladder is dissected from the liver bed and removed through the umbilical incision. Incisions are closed with sutures.

Large stones are removed by opening the gallbladder outside the abdomen or fragmenting them if necessary. Occasionally, the incision is slightly enlarged.

A drain may rarely be placed, especially in acute cases, and is usually removed the next day if no bleeding is detected.

POSTOPERATIVE PERIOD

Liquids are started 4 hours after surgery, solid food after 12 hours. Patients are mobilized after 6 hours. Pain is mild and usually resolves within 2 days. Discharge is typically after 24 hours. Sutures are removed after 7 days. There is no special postoperative diet, and routine follow-up is unnecessary unless symptoms occur.Figure: Gallstones in the gallbladder and stones obstructing the cystic duct and common bile duct

* Obstruction of the cystic duct → gallbladder distension and infection

** Obstruction of the common bile duct → obstructive jaundice

What Should Be Done If Stones Are Detected Simultaneously in the Common Bile Duct and the Gallbladder?

This is an important detail. As explained previously, stones in the common bile duct are treated endoscopically using the ERCP method. However, it is not possible to intervene on stones inside the gallbladder with ERCP.

After the bile ducts are cleared with ERCP, the gallbladder together with the stones it contains is removed through a laparoscopic or open surgical operation, thereby permanently resolving the problem. If the attempt to clear the bile duct with ERCP fails, the only option is open surgery, during which both the bile duct is cleared and the gallbladder is removed. Leaving a gallbladder containing stones in the patient after clearing the bile duct with ERCP is not an appropriate approach. This is because the only problem caused by gallbladder stones is not merely the passage of stones into the common bile duct, as explained in detail above.

The main advantage of clearing the bile ducts with ERCP is avoiding the difficulty and complications of open bile duct surgery and enabling the patient to return home in a very short time after a laparoscopic (minimally invasive) gallbladder operation (9).

Does Removal of the Gallbladder Cause Any Problems? Is a Special Diet Required?

No complaints related to the absence of the gallbladder or any long-term proven side effects are known. A person usually notices the absence of the gallbladder because they no longer experience the problems they previously had.

After gallbladder removal, no special diet is required. Claims such as “fried foods or eggs should not be eaten” have no medical basis. I tell my patients, “If your neighbors tell you not to eat eggs, you can eat their eggs as well.”

What Is the Relationship Between Gallstones and Gallbladder Cancer?

There is evidence that gallstones larger than 3 cm that remain in the gallbladder for many years (more than 15 years) may cause gallbladder cancer (10). In other words, stones of this size may remain silent for many years, but unfortunately may one day present as gallbladder cancer, which is very difficult to treat. For this reason, especially large gallstones should be removed surgically, even if they do not cause any symptoms.

Summary

- The frequency of gallstones increases with age.

- They may remain silent for years or lead to life-threatening complications.

- Gallstones that have caused symptoms once have a high likelihood of causing problems again; therefore, removing the gallbladder before complications develop is the most appropriate approach.

- The ideal treatment is laparoscopic (minimally invasive) removal of the gallbladder.

- There are no known side effects of gallbladder removal.

- No special diet is required after gallbladder removal.

- Large gallstones are known to be associated with gallbladder cancer.

References

- Schirmer BD, Winters KL, Edlich RF. Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2005;15(3):329–38.

- Carey MC. Pathogenesis of gallstones. Recenti Prog Med. 1992 Jul–Aug;83(7–8):379–91.

- Özkan S, Bodur H, Alponat A. Choledocholithiasis in pregnancy. Türkiye Klinikleri J Gynecol Obst. 2006;16:105–110.

- Ploneda-Valencia CF et al. Gallstone ileus: An overview of the literature. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2017 Jul–Sep;82(3):248–254.

- Goh PMY, Alponat A, Kum CK. Super minimally invasive laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Asian Journal of Surgery. 1998;21(1):12–14.

- Alponat A et al. Is minisite cholecystectomy less traumatic? World J Surg. 2002;26(12):1437–40.

- Tiryaki C et al. Ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A single-center experience. J Minim Access Surg. 2016;12(1):47–53.

- Alponat A et al. Predictive factors for conversion of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 1997;21(6):629–33.

- Alponat A et al. Predictive factors for synchronous common bile duct stones in patients with cholelithiasis. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:928–932.

Andrea C, Enzo A. Cholesterol gallstones larger than 3 cm appear to be associated with gallbladder cancer. Ann Surg. 2016;263(3):e56.

Hello, I am Prof. Dr. Ahmet Alponat, a General Surgery Specialist. I provide patient care in the fields of Laparoscopic Surgery, Gastrointestinal and Breast Oncologic Surgery, and Interventional Endoscopy.

You can receive services both at Acıbadem Kocaeli Hospital and at my private practice in Bodrum. To contact me, please visit the Contact page. If you have any questions about the article you have read, you may submit them using the question and comment form located at the bottom of the page.