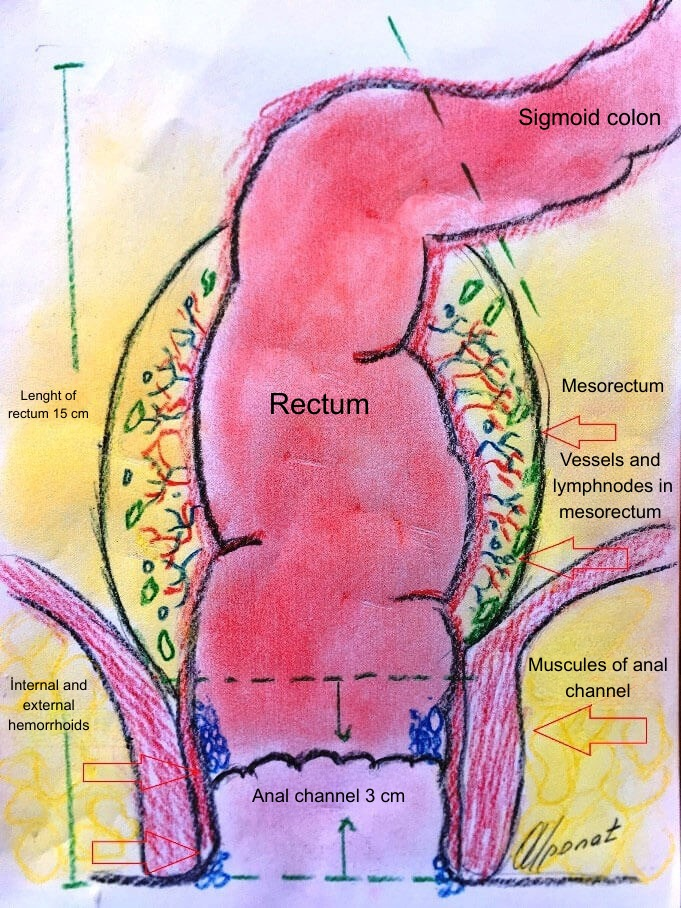

The rectum is the final portion of the large intestine, ending at the anus. It is 12–15 cm long. The last 3 cm is the anal canal. The anal canal is surrounded circumferentially by two separate muscle groups that allow us to retain stool. Cancers of the anal canal differ in certain aspects from rectal cancers. I will briefly address this topic later. In addition, non-cancerous diseases of the anal region can be found on my website under the headings “hemorrhoids, anal fissure, anal abscesses, perianal fistulas, and genital warts.”

Figure. Normal rectum and anal canal anatomy

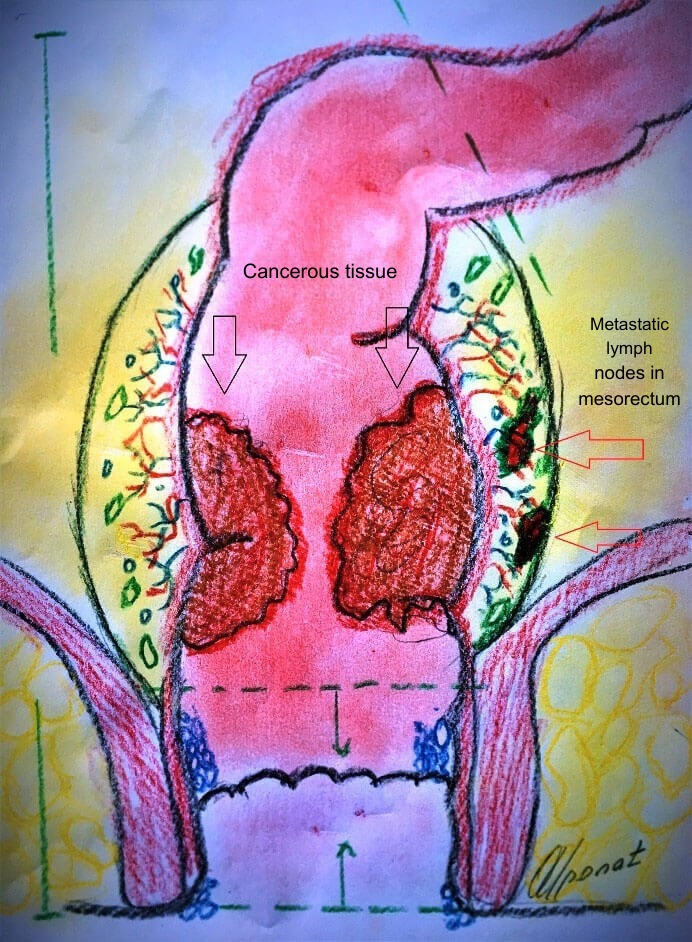

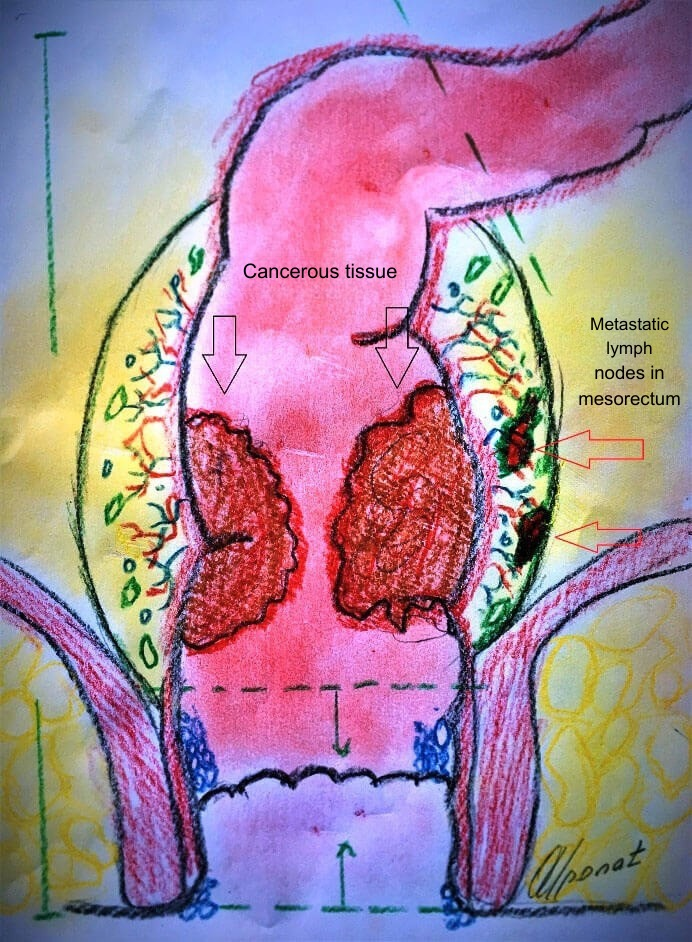

The rectum is completely surrounded by a fatty tissue called the mesorectum, which contains the blood vessels supplying the rectum and lymph nodes. As will be discussed later, this structure is of great importance in rectal cancer surgery. The mesorectum surrounds the entire rectum, excluding the anal canal. From a surgical anatomy perspective, the rectum is divided into three parts: lower, middle, and upper rectum.

The location of the cancer is defined by taking the anal verge as the “0” point and determining how many centimeters above this point the tumor is located. For example, during rectal examination with a rectoscope, when the tip of the scope reaches the tumor, the distance visible on the scope at the level of the anal opening (such as 5 cm, 8 cm) indicates how far the tumor is from the anal verge. This measurement is very important. Tumors located within the first 3 cm from the anal verge (i.e., within the anal canal) require irreversible removal of the anus, resulting in the necessity of carrying a permanent stoma (bag) for life. In tumors located higher up, after removal of the tumor-bearing segment, it may be possible to reconnect the healthy bowel above to the anal canal, allowing continued use of the natural anal route.

The factors causing rectal cancer, the cell types involved, and prevention strategies are almost identical to those of colon cancer and therefore will not be discussed again here. However, the treatment approach and surgical techniques for rectal cancer differ in some respects. This is because in some rectal cancer cases, patients may be permanently dependent on a stoma, meaning lifelong diversion of stool into a bag attached to the abdominal wall. In addition, some complications specific to rectal cancer surgery may occur that are not seen in colon cancer surgery.

Symptoms of Rectal Cancer

Symptoms of rectal cancer show some differences compared to colon cancer:

Bleeding:

The most common complaint is bleeding. Blood is usually seen mixed with or coating the stool, but it may also occur before or after defecation. Some patients report passing jelly-like clots of blood.

Sensation of incomplete evacuation (tenesmus):

One of the most important and striking complaints. The patient feels the urge to defecate but is unable to pass sufficient stool when sitting on the toilet. This may recur many times during the day.

Narrowing of stool caliber:

As the tumor narrows the rectum, the diameter of the stool decreases. Patients often describe this as “my stool has become pencil-thin.”

Rectal Examination and Diagnostic Tests

In patients with such complaints, digital examination of the anal canal and rectum (digital rectal examination) is essential as the first step. A large proportion of rectal cancers can be diagnosed this way. However, the finger can reach only about 8–10 cm. Tumors located higher than this can only be diagnosed by endoscopic examinations (colonoscopy/rectoscopy). During these examinations, tissue samples are taken for pathological analysis.

If the pathology report confirms cancer, the next step is staging the disease. The most appropriate test for staging is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI reveals whether the cancer has penetrated the rectal wall and whether it has spread to surrounding lymph nodes. Another important test is positron emission tomography (PET), which allows whole-body scanning to detect distant metastases.

Treatment Planning

If the cancer is limited to the rectal wall, the disease is at an early stage (Stage I–II) and direct surgical treatment can be performed. If the tumor has invaded the fatty tissue surrounding the rectum (mesorectum) and there are lymph nodes containing tumor cells in this area (Stage III), the patient first receives radiation therapy (radiotherapy) and drug therapy (chemotherapy). This treatment lasts approximately one month and is called neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Its purpose is to shrink the tumor and reduce the risk of tumor spread during surgery.

After this treatment, no further therapy is given for 8–12 weeks, and then appropriate surgical treatment is performed depending on the tumor’s location in the rectum.

Surgical Treatment

The procedure involves removing the rectum together with the surrounding fatty tissue (mesorectum). This is called Total Mesorectal Excision (TME). The most critical issue is whether the anus can be preserved:

- If the tumor is within the first 3 cm from the anal verge, removal of the anus is unavoidable, and the patient must carry a permanent stoma for life. This procedure is called abdominoperineal resection.

- If the tumor is within the first 10 cm from the anal verge, the operation involves removal of the rectum and surrounding fatty tissue, followed by reconnection of the healthy bowel above to the anus (Total Mesorectal Excision and coloanal anastomosis).

- If the tumor is located between 10 and 15 cm from the anal verge, a partial mesorectal excision is performed, and the healthy bowel is connected to the remaining rectum.

Figure. Advanced rectal cancer and lymph node metastases

Figure. After complete removal of the rectum with tumor tissue, reconnection of the pulled-down healthy bowel to the anal canal

If radiotherapy has been given and surgery is planned afterward, a temporary stoma (temporary ileostomy) may be recommended after tumor removal and reconnection to the anus to reduce the risk of leakage from the anastomosis. This is because patients who have received radiation therapy have a higher risk of leakage at the connection site.

With the application of the treatment methods mentioned above, the problem of tumor recurrence—one of the major issues in rectal tumors—has significantly decreased, and postoperative complication rates have been reduced.

Such delicate and specialized surgical procedures are extremely important in determining postoperative quality of life. While colon surgery may not involve many critical details for a surgeon, rectal surgery is a specialized field, and extensive experience is one of the most important factors influencing outcomes. Surgery in this area carries significant potential complications, including:

- Leakage of stool from the anastomosis (anastomotic leak),

- Injury to nerves supplying the reproductive system and bladder, leading to:

- Erectile dysfunction in men,

- Retrograde ejaculation or inability to ejaculate,

- Urinary dysfunction due to bladder atony,

- Vaginal dryness and inability to achieve lubrication during intercourse in women.

Apart from these extensive surgical approaches, in very early-stage small rectal cancers, it may be possible to remove the tumor directly through the anus using special instruments (local excision of the tumor). However, such early-stage tumors are rarely encountered in our country, as patients often seek medical care late.

A brief note on anal canal cancers:

Cancers of this region arise from cell types different from those of colon and rectal tumors. These cells are highly sensitive to radiation therapy. Therefore, in most cases, the primary treatment is a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Surgery is considered only when radiation therapy fails.

SUMMARY

As seen, rectal cancers differ from colon cancers in several respects:

- Radiotherapy may be used before or after surgery in rectal tumors, whereas radiotherapy has no role in colon tumors.

- In rectal tumors very close to the anus, a permanent stoma (colostomy) may be mandatory, while colon tumors do not require a permanent stoma regardless of their location.

- Preoperative radiotherapy in rectal tumors can shrink the mass, making it possible to preserve the anus in some tumors close to it.

- Leakage from the anastomosis after rectal tumor surgery is more frequent and troublesome than in colon tumor surgeries.

- Side effects affecting reproductive and bladder functions may occur after rectal tumor surgery but are not seen in colon tumor surgeries.

- Thanks to surgical and oncological advances in the treatment of rectal tumors, post-treatment survival has significantly improved, and the former pessimistic outlook has largely disappeared.

REFERENCES

- P. Gordon. Colon cancers. In Principles and Practice of Surgery for the Colon,Rectum and Anus.3rd edit., New York, pp: 489-625, 2006.

- Kobiela J, Spychalski P, Wieszczy P, Pisera M, Pilonis N, Rupinski M, Bugajski M, Regula J, Kaminski MF. Mortality and Rate of Hospitalization in a Colonoscopy Screening Program From a Randomized Health Services Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Sep 13. pii: S1542-3565.

- Tamandl D, Mang T, Ba-Ssalamah A. Imaging of colorectal cancer – the clue to individualized treatment. Innov Surg Sci. 2018 Mar 13;3(1):3-15.

- Cao Y, Gu J, Deng S, Li J, Wu K, Cai K. Long-term tumour outcomes of self-expanding metal stents as ‘bridge to surgery’ for the treatment of colorectal cancer with malignant obstruction: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Ebigbo A, Probst A, Messmann H. Endoscopic treatment of early colorectal cancer – just a competition with surgery? Innov Surg Sci. 2017 Nov 8;3(1):39-46. doi: 10.1515/iss-2017-0037. eCollection 2018 Mar. Review.

- Horvat N1, Petkovska I2, Gollub MJ. MR Imaging of Rectal Cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2018 Sep;56(5):751-774. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2018.04.004. Epub 2018 Jul 11.

- Bullock M, Nasir IUI, Hemandas A, Qureshi T, Figueiredo N, Heald R, Parvaiz A. Standardised approach to laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a prospective multi-centre analysis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2019 Aug;404(5):547-555. doi: 10.1007/s00423-019-01806-w. Epub 2019 Aug 3.

- Ludmir EB1, Palta M2, Willett CG2, Czito BG2. Total neoadjuvant therapy for rectal cancer: An emerging option. Cancer. 2017 May 1;123(9):1497-1506. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30600. Epub 2017 Mar 10.

Hello, I am Prof. Dr. Ahmet Alponat, a General Surgery Specialist. I provide patient care in the fields of Laparoscopic Surgery, Gastrointestinal and Breast Oncologic Surgery, and Interventional Endoscopy.

You can receive services both at Acıbadem Kocaeli Hospital and at my private practice in Bodrum. To contact me, please visit the Contact page. If you have any questions about the article you have read, you may submit them using the question and comment form located at the bottom of the page.